|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

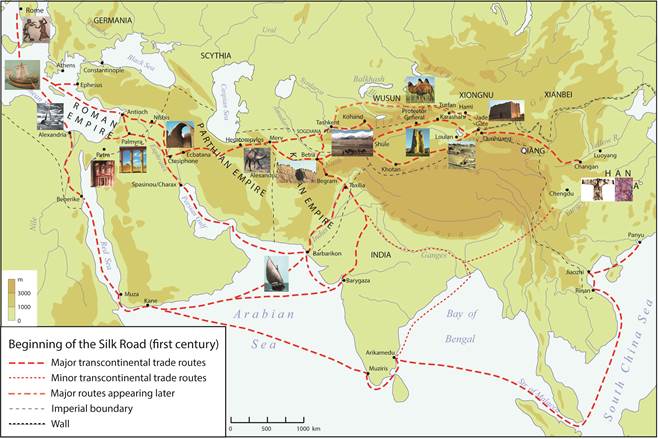

The

beginning of the Common Era was the age of empires. The Roman, Parthian, Kushan,

and Han Empires maintained significant stability across Eurasia. Imperial

prosperity stimulated consumption, which stimulated exchange. Gradually, a

patchwork of long distance trade routes emerged. The Silk Routes at the time of the Roman Empire (27 BCE

– 476 CE) and Han Dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE) differed in several ways from

that of later times. First,

the residual power of the Xiongnu

blocked the northern routes that would flourish since the seventh century,

when the Byzantium Empire, Islamic

Caliphate, and Tang Dynasty maintained another period of

cosmopolitanism.

Second, most trade combined land and sea legs. Third, the initial

purpose of Han activities in the western regions was to counteract the Xiongnu. Thus much of its export served political rather

than commercial interests. From

Changan (today’s Xian) capital of the Former Han,

the Silk Road passed through the thousand-kilometer-long Hexi

Corridor between mountains and deserts. Beyond the Jade Gate that guarded the

western terminus of the Corridor, in now China’s Xinjiang province, the Han

established the Protectorate of Western Territory after a long struggle with

the Xiongnu. There the route split to follow two

strings of oasis. They converged at Shule (Kashga) at the eastern foothill of the Pamir. Crossing

the Pamir along broad valleys, travelers arrived at the Ferghana

Valley, home of superb horses, and Sogdiana, home

to many long-distance traders. Alternatively, they could take the Khunjerab high pass and go directly to Bactra (Balkh) in Bactria, a trading hub until

the Mongols destroyed it. From

Bactria, west-bound caravans headed for Parthia, where they picked up the

Persian Royal Road, passed Ctesiphone, and brought

trade goods to Syria for the Roman market. This is the poster image of the

Silk Road. At its beginning, however, the Silk Road had a twist. The Kushans who ruled Bactria and today’s Pakistan had other

ideas. They directed the goods from China to the south, across the Hindu

Kush, down the Indus River, to the ports of northwestern India, where the

merchant fleets from the Roman realm waited. Egyptian

traders brought the goods up the Red Sea to Alexandria, thus avoiding Parthia

altogether. However, the leading long-distance traders in the Roman realm

were the Arabs who founded the oasis city of Palmyra. Palmyrene

traders organized caravans as well as fleets. From Indian ports, they brought

the goods up the Persian Gulf, then through Parthian territory to Syria. When

Palmyra revolted, Rome destroyed it in 273, dealing a grievous blow to its

eastern trade. Rome

imposed a 25 percent import duty. The Han did not tax foreign trade. However,

the literati-officials who dominated the Latter Han had scant interest in the

outside world and were eager to close the Jade Gate and abandon the Western

Territory to the Xiongnu. It was almost a personal

effort to reestablish the trade routes after decades of disruption. Ban Chao

persuaded the government to send 1,000 soldiers and augmented this core force

by mobilizing native troops. In ten years of strenuous fighting, he

re-pacified the Western Territory. Then, in 97, he dispatched a deputy, Gan Ying, in quest of Daqin,

the Roman Empire as it was called by the ancient Chinese. Gan

reached Mesopotamia, where he turned back for unclear reasons. That was

eighteen years before the Roman Emperor Trajan marched into Mesopotamia. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|