|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

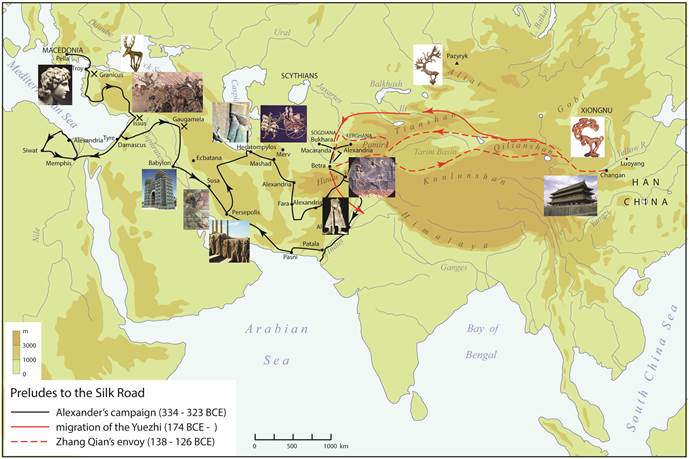

Peoples

had been interacting and trading with each other in prehistoric times. An

evidence of exchange among peoples of the great Eurasian steppe is the common

form of the “cosmic deer” that decorated pole tops and other standards. The

oldest relic recovered is the 2400-2000 BCE bronze stag,

from Alaca Hüyük,

Anatolia. The fourth century BCE tomb at Pazyryk

yielded a reindeer with outsized antler. Several specimen of similar vintage

were found in tombs of northern China, especially the Ordos region (left

two). The gold figurine with the most ornate antler is from Nalin gaotu, Shenmu county, Shaanxi. |

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

In

the fifth century BCE, today’s Afghanistan was a part of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Persian influence is testified by the Oxus

treasure, a horde of artifacts excavated besides the River Oxus (Amu Darya).

Bactria, the land with a thousand cities, was especially prosperous. |

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Then,

In 329 BCE, Alexander the Great came to Transoxiana, land beyond the River Oxus. Here he adopted

Persian ceremonies and found his only Queen, Roxane.

Here he met also his fiercest resistance. Besides locals, his enemies also

include Scythians, nomads of the steppe. Soon after Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, his empire split into three kingdoms: Macedon, Egypt, and the Seleucids

in the east. Since the mid third century BCE, the Seleucids came under the

pressure of the Parthians, a semi-nomadic people from the northeast who, led

by the house of Arsacid, gradually took over now

Iran, then Iraq, until they set up their winter capital Ctesiphon south of

today’s Baghdad

in 141 BCE. The Parthian Empire lasted until 224 CE, when it was overthrew by

the Sassanid Persians, descendent of the Persian Empires destroyed by

Alexander. The

Greeks who remained in Central Asia established the kingdom of Bactria and

spread Hellenic culture. Nevertheless, they were not immune to native

influences. In Ai Khanum, at the border between

Afghanistan and Tajikistan, archeologists uncovered the ruin of a

third-century Greek city complete with Corinthian colonnades and a large

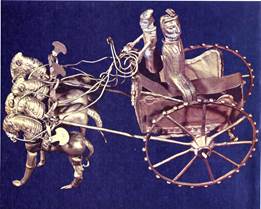

gymnasium. Its artifacts, for example the ceremonial silver plate showing the

Greek goddess Cybele on a lion-drawn chariot before an stepped Asian-style

alter, expressed the blending of cultures. |

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Meanwhile,

events were accelerating at the eastern and western ends of Eurasia. In 221 BCE, when Rome’s toughest enemy Hannibal took command of the

Carthaginian army, Qin unified China by conquering six states that had been

warring with it and each other for centuries. In

215 BCE, the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty expelled the nomadic Xiongnu

from regions south of the long walls built by the former states. However,

even reinforced walls could not prevent the Xiongnu

from overrunning much territory during the anarchy that followed the Qin’s collapse

in 206 BCE. The Han Dynasty, which succeeded the Qin,

bought partial peace by paying tribute and presenting princesses to the Xiongnu for more than seven decades. The Xiongnu had

emerged as a steppe power

in the third centuries BCE by integrating

semi-autonomous nomadic

tribes into a federation. Among its victims was the Yuezhi, whose rich pastures north of the Qilian Range the

Xiongnu annexed. Fleeing west, the Yuezhi drove the Sai people

from the Ili Valley, but had to run themselves when their old enemies came

after them in 162 BCE. The Xiongnu made the skull

of their king into a drinking cup and the Wusun,

their former neighbor in the Qilian, took over Ili. Kicked out again, the Yuezhi

swept south through Transoxiana. Known as Tokhari in western sources, the Yuezhi

were among the best known of the nomads who took Bactria from the Greeks.

They attacked the Greeks in the 130s BCE and overran Bactria in the following

decades. The Kushan Empire they founded, which

extended into present Pakistan and northern India, lasted until 225. The Han, too, came after the Yuezhi, but as an ally. Wudì,

who acceded the throne in 140 BCE at age seventeen,

decided that China had suffered enough humiliation from the Xiongnu. He dispatched

Zhang Qian to seek the Yuezhi

for an anti-Xiongnu alliance. Zhang fell into the

hands of the Xiongnu, who pressed on Han territory

on the north and northwest. Escaping after ten

years’ detention and making his way through Ferghana

and Sogdiana in today’s

Uzbekistan, he reached the Yuezhi north of the Oxus in 128 BCE, but was disappointed

to find them happily lording over the Bactrian Greeks,

with no intention to cooperate with the distant Han and settle their grudge

against the terrible Xiongnu. Nevertheless, he

brought back something most valuable, intelligence about western countries.

Based on them, the Han formulated a strategy to augment military operations

with diplomatic and economic efforts aimed to deprive the Xiongnu

of the support and resources of these countries. Zhang Qian

led a large team on his second western mission, laden with gold and gifts. Parthia received a Chinese envoy and returned an embassy in 113 BCE.

A few years later, the first silk-bearing caravan arrived from the east via

Bactria. The

Romans invaded Parthia in 53 BCE. Their army led by Crassus was annihilated

in the battle of Carrhae at the upper Euphrates.

Here the Romans first encountered nomadic mounted archers. From their

experience of horsemen at full gallop shooting backward at their pursuers

came the idiom “Parthian shot” as the ultimate putdown. Some say the legions

were also amazed by Parthian banners made of silk. Whether it is true or not,

silk did reach the Mediterranean around this time. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

|