|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The Rise and Fall of the Roman and Early Chinese

Empires Two

thousand years ago, the Old World of civilization underwent its first

imperial age. The Roman Empire and the Han Dynasty of imperial China

coexisted with Parthia and Kushan, spanning the mid-latitude of Eurasia and

northern Africa. The four empires maintained certain world order and

stimulated the rise of transcontinental trade later known as the Silk Road. However, the

Roman Empire and Han China never established direct relationship because of

the great distance and rival powers between them. Individual histories for

each abounded, but until recently, few attempts existed to compare the two.

It

would be frivolous for historians to speculate what would happen if Eurasia

were smaller and the Romans found beyond their eastern frontier not Parthia

but China. Yet as the New World expands the political horizon, new

technologies contract effective political distances even more. In view of

contemporary global power balance, comparison takes on new significance. At

the formative periods of the western and eastern styles of exercising

imperial power, the ancient empires left rich and influential legacies. China

pulled through numerous fragmentations and invasions, and remains a unified

nation. The Roman Empire did not recover from its fall, but its will to power

and many ideas have become “cultural genes” of western culture. The United

States is sometimes called a “New Rome”. In the global village, the heirs to

the ancient empires must interact closely, and for that, to know each other,

including their traditional roots. What were the characteristics, the

respective strengths and weaknesses of the ancient superpowers of the east

and west? The rise of the Roman and Chinese empires were

arduous and lengthy processes that took at least four centuries. In the

eighth century BCE, the geopolitics of eastern Asia was similar to that of

the eastern Mediterranean, which was populated by hundreds of tiny Greek

city-states. Five years after the Greeks gathered for their first Olympic

Game in 776 BCE, the host of centuries-old city-sized feudal states in China

received a new company, Qin, the future empire builder. Eighteen years after

the investiture of Qin, tradition had it that Rome was founded on the hills

beside the River Tiber. The legend’s veracity is much questioned, but it was

around this time that the Greek and Phoenician colonizers brought the model

of city-state to the western Mediterranean and founded Carthage, Rome’s

future arch enemy. The foundation of the Republic in 509 BCE was undoubtedly

a turning point in Rome’s history. It too, found itself among a host of

city-states in Italy. This was the age of hegemony. Strong states annexed neighboring land when

convenient, but mostly they tried to win not territories but allies, whom

they led to fight rivals. When administrative institutions were not yet

developed to manage large populations, allies that took care of their

domestic affairs but obeyed orders in foreign affairs were more effective for

the hegemon to expand its power. Strong states in China vied to become ba or the hegemon, the leader of

lords. Rome had conquered Italy before it expanded overseas, but until the

Social War of 91-87 BCE, it preferred to be the hegemon of Italian allies,

from whom it demanded troops to fight under its command. The age of large territorial empires were coming,

but first to the middle region of Eurasia. The Persian Empire was repelled by

the Greeks, then destroyed by Alexander the Great in the 320s BCE. Like its

Persian predecessor, Alexander’s empire reached the western slopes of the

high Pamir, but not beyond. At that time, seven warring states were busy

fighting each other in eastern Asia. To the west of the empire, the Roman

Republic was busy fighting the Samnites, mountain folks in central Italy. The

ephemerality of Alexander’s empire highlights the greatest achievements of

the Roman and Chinese empires, their stability and longevity.

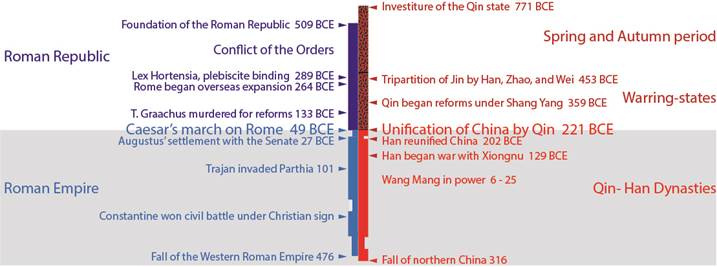

The Roman and early Chinese empires were not

exactly simultaneous, but their chronology overlapped.

The unification by Qin was the definitive turning

point in Chinese history, which initiated its imperial age. The Republic led

Rome to acquire an empire in less than five centuries, before Julius Caesar

started the civil war that destroyed it. For the purpose of comparing two

careers of rise and fall, it is convenient to shift their relative timelines.

I match up the unification of China in 221 BCE and Caesar’s march on Rome in

49 BCE, so that we can talk about the progress of their “imperial age”, here

shaded in grey.

The Roman and Chinese had much similarities but

also many differences. Their economies

were both agrarian and monetized, but adopted different models of production

organization. Their societies were both patriarchic, conservative and

stratified. Each person had specific social roles and had moral duty to be

contended with them. Both societies valued the family, the nursery of authoritarianism,

but the Roman made a clear legal separation between the state and the family,

the Chinese did not. Their political power was mostly held by aristocrats,

but the Roman senatorial aristocracy and the Chinese feudal aristocracy

differed in characters. Initially, their states were all city-sized, but the

western city-state and Chinese feudal states had different political

structures. In the course of rise to empire, Rome and China

each undertook technological and economic development, cultural transformation,

political reform, and conquest, which depended much on military organization

and the government’s capacity to mobilize and direct resources. Because the

conditions of the infant Republic and the early Spring and Autumn period were

so different, and because the two realms undertook radical reforms in

different stages of development, their rises followed different paths, and

ended in two forms of absolute monarchy, a military dictatorship with wealthy

elites for the Roman Empire, a bureaucratic autocracy with doctrinaire elites

for imperial China. The five centuries prior of unification of China

were divided into two periods, traditionally called the Spring and Autumn

period (named after the Spring and

Autumn Annals complied by Confucius, an aristocrat who lived toward its

end) and the Warring-states period. In terms of technology, economic

development, and political organization, China in the Spring and Autumn

period lagged far behind that of the early Roman Republic. It caught up

during the Warring-states period, when Legalist reformers prepared the

institutional foundations of the imperial China. China in the Spring and Autumn period was still in the late bronze age. Its main weapon was the chariot, which was monopolized by aristocrats. Its economic and political organizations were “feudal”. Private landed property right was unknown; land ownership was undifferentiated from fiefdom and political sovereignty. People lived their lives in communal farms and collectively worked the seigniorial fields without compensation. Individual families used allotted plots for subsistence but did not own them; the plots were rotated among families for fairness. There was no market for land. The more than a thousand fully independent tiny states were descendants of fiefdoms erected in the eleventh century BCE by the king of Zhou. Their rulers, mostly distant relatives, still retained the title of lords and paid lip service to the now powerless king. Each lord in turn parceled out his realm into fiefs for vassals, who also served as his ministers. The hereditary ministers owed loyalty to their lord only, not to the king. Thus although the king had notional authority over the world, substantive authority was distributed among feudal aristocrats, the lords and their ministers. The state was undifferentiated from the ruling family. All ministries were hereditary, many held their own fiefs, and most were relatives to the ruler. Qinqin, the love of relatives, was the prime political principle. Aristocrats punished offenders, but had no published laws to regulate the application of punishments. They deemed their personal discretion sufficed because of their superior status and virtue. The big achievement of the Spring and Autumn was high culture. Centuries of easy life had bred polished aristocrats who quoted poetry in banquets and political discourses. Their texts would become Confucian Canons, which would provide a moral gloss of their rituals and standards. The precociousness of high culture relative to political and economic developments enabled bronze-age ideals to be frozen into the tenets of Confucianism and sway imperial China for more than two millennia. The rule of man and family values would continue to be the center of political principles. Challenges did come in the warring-states period. Iron appeared. Effective and affordable tools spread, elevating productivity. Land previously uncultivable yielded to the plow. Independent family forms emerged. Aristocrats found it increasingly difficult to have their seigniorial domains tended. Meanwhile, the city-sized states gradually coalesced into large territorial states. Growing population and prosperity increased social complexity. Powerful ministers grew seditions ideas. Intense interstate competition created a sellers’ market for talents and the most vibrant ferment in Chinese intellectual history. Meritocracy challenged aristocracy. Able pragmatists instituted reforms in various states to improve administration and provide some rational direction for the newly unleashed social energy. They experimented with different ways to cope with local difficulties, but were generally called Legalists for their shared novel idea: the rule by laws and equality under the law. The most famous Legalist was Shang Yang, who integrated the experiences of his predecessors. His reforms in Qin, beginning in 359 BCE, not only brought Qin from an underdog to the major league of warring states, but also set the institutional foundation for imperial China. Legalist reformers led land-reclamation and waterworks projects. To encourage small independent farms, the state systematically distributed land to individual families in return for tax and service in the infantry, which replaced chariots on the battlefield. Private land ownership began to spread. Prosperous farmer-soldiers rejoiced at the chances to prove their valor and win the government’s reward for it. Legalists also built up bureaucratic offices for efficient management and rules for secure delegation of power. The development of an effective civilian bureaucracy before the scale of wars escalated in the late-warring states period partly explained why, unlike the Roman world, prolonged and intense warfare did not breed an army that went beyond government control to the benefit of military dynasts. To govern expanding population and territory, the state instituted provinces with centrally appointed governors selected on ability and merit, who replaced feudal aristocrats in local administration. All these curbed the aristocracy and centralized power on the king. Furthermore, Legalists issued regulations for government officers and meted out punishments for abuses, even to aristocrats and relatives. The rule by laws earned them the hatred of aristocrats, who condemned it for cruelty and immorality. When Qin united China, the First Emperor abolished the feudal aristocracy and ruled the empire through a centralized bureaucracy. This was the lasting contribution of the Legalists, but it had to suffer bitter reactions from Confucians. In contrast to the elegant aristocrats of feudal China, the senatorial aristocrats of the early Roman Republic were rustic and pragmatic. They were farmer-soldiers like common citizens, as symbolized by Cincinnatus, patrician and consul who labored in the field himself. The Mediterranean world was well into the Iron Age. Affordable effective tools and weapons empowered the common producers and warriors. Self-equipped military service was the foremost duty of a Roman citizen. The Centuriate Assembly, the Republic’s democratic arm, met in the military training ground. Conscious of their contributions, the commons demanded a larger say in public affairs. During the first two centuries of the Republic, the commons organized an assembly of their own, resisted arbitrary coercive power of the aristocrats, and won for themselves significant liberty. The “conflict of the orders” produced a republican constitution, in which the aristocrats exercised collective rule through the Senate, but their power was checked and balanced by the popular assemblies. In annual elections, the assemblies selected magistrates from aristocratic candidates. They also voted to pass or reject bills that aristocrats presented to them, but they had no right to propose or amend bills, or to speak singly in assembly. A peculiar feature of the republican constitution was its wealth-based politics. Periodic census divided the citizen bodies according to their wealth. The weight of a citizen’s vote was proportional to his wealth, and only the wealthiest were eligible for the Senate and magistracies. The union of wealth and political power was a Roman characteristic that persisted through the Republic and Empire. Not surprisingly private property rights were sacrosanct and a central concern of Roman laws. The people’s assemblies made the ultimate decision on war or peace. For centuries, they almost annually voted for war, showing a deep militarism surpassing that of both the Greeks and the Chinese. Roman wars were mainly financed by indemnities exacted from losers plus systematic looting and enslavement. Abundant booties from the rich Hellenistic world enabled the government to exempt Italian land from tax. This may not be a blessing for the common people. Generals and provincial governors, who were already rich and powerful, grabbed the lion’s share of the booty and used it to buy up or appropriate farmland. Large plantations worked by slaves exerted crushing pressure on small independent farms. Many proud proprietary farmers who marched out with the legions returned to find themselves dispossessed. Economic inequality skyrocketed. More and more citizens lost their land and their means to purchase weapons for military service. Repeated agrarian reforms aimed at mitigating the situation failed because of staunch aristocratic opposition. Conscription faltering, the army turned to recruit volunteers from the poorest strata of society. The city-state government had no means to prevent ambitious generals from buying off the army by looted silver and the promise of land at retirement. The Republic’s failure at timely political reform paved the ground for the military dictatorship of the Empire. A summary of the pre-imperial developments:

From their republican or and feudal origin, Rome and China converged on absolute monarchy. In the Roman and Chinese Empires, all authority in the vast realm devolved on the emperor. However, absoluteness is not omnipotence. No mere mortal can exercise this unbound authority. To turn authority into power and govern effectively, the emperor needed the cooperation of the ruling elite to secure the compliance of the people. Much politics of the late imperial periods was fueled by struggles between aristocrats and monarchists bent on centralizing power. In the empires, the emperor and the ruling elites gradually came to terms with each other. Together they evolved autocracy at the expense of the people. Julius Caesar grabbed dictatorial power on the support of his mighty war machine. But his inability to placate senators attached to the republican ideal of aristocratic collective rule led to his assassination. His heir took the lesson to heart. Augustus put on a republican facade and played courtesy to senators, even as he stripped all power from the Senate and the assemblies. He heightened the wealth qualification for senators, so that only the extremely rich could enter government service. Roman citizens lost all political rights. Social privileges gradually shifted from citizenship to wealth. Although the early Roman emperors called themselves princeps or first citizen, the Greeks correctly recognized them as the autocrat, the ruler answerable to none. The emperor’s power was protected by the Praetorian Guard and a large professional army that had sworn loyalty to his person and his family. His words acquired the force of law. His right to power was never legally challenged or tested in the Senate; usurpation and mutiny were the only threats. Authority was secure not only for him but also for his family. No emperor who had a biological son living was ever succeeded peacefully by anyone else. Some emperors were succeeded by adopted sons, but the problem lay not with the hereditary principle but with the low fertility of Roman aristocrats. Qin’s abolition of the feudal aristocracy incited such resentment that he had to burned books to suppress opposition. It did not work. After rebellions toppled the Qin dynasty, the Han dynasty reinstituted the feudal aristocracy to placate the elites, whose dream was to become lords or hereditary ministers. It worked for three generations before the lords became restive, threatening a return to the warring states. The emperor quashed the rebels. A centralized government finally ruled over the whole empire a century after Qin’s first attempt. This time it lasted. The bureaucracy designed by Legalists became the permanent institutional structure of imperial China. The emperor bought off the elites by making Confucianism the state ideology. Soon doctrinaire literati colonized the bureaucracy, condemned Legalist rule by laws, subverted rational regulations by personal connections, and the preached the virtue of deference to superiors. With their indoctrination machine, the Confucian literati officialdom became arguably the most successful conservative ruling elite in world history. The histories of Rome and China show that there

is no single panacea for world history. Contrary to today’s saying that all

nations must converge toward democracy and the rule of law, the Romans

actually turned away from it. For peace and stability, for the benefits of

the ruling circle, the Roman Empire sacrificed the democratic elements of the

Republic, including the citizen’s political rights and the transparent

legislative process underlying the rule of

law. Nevertheless, the Romans characteristically extolled general law

abidance and adhered to the rule by laws.

Imperial China never developed the idea of rule of law. Legalists introduced

the rule by laws, but the equality under existing laws infringed on the

privileges of ruling elites who upheld the ideals of feudal aristocrats. When

Confucianism became the state ideology in the Han dynasty, imperial China

sacrificed its nascent rule by law. Instead, it opted for the rule of

“virtue” supplemented by punishments. Characters of the Eagle and Dragon, the Roman and Chinese styles of rule: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Details of the above outline can be found in The Dragon and the Eagle: the rise and fall of the Roman and Chinese Empires. |