|

Coinage

and the economy in the Roman and Early Chinese Empires

The Roman Empire was more monetized than the Qin-Han Dynasty, but

even the latter was more monetized than most ancient agrarian economies. The

Romans minted coins of gold, silver, and bronze. The Chinese Empire issued

only bronze coins; gold and later silver were used as ingots.

|

|

|

1. Roman coins.

|

|

|

|

2. Chinese coins.

|

|

|

The Roman coinage doubled

as a propaganda tool. Coins were frequently melted down and re-struck,

bearing current messages. The most common designs were the image of the

emperor or other grandees. (a) Image of Julius Caesar, with the inscription

proclaiming his status as dictator. (b) Imperial image of Augustus standing

on the globe. (c) Coin in the eastern provinces celebrating Augustus’

annexation of Cleopatra’s Egypt. (d) “Judea Morning”, issued 69-70CE upon

suppression of a Jewish revolt. (e) Image of Rome’s founding myth: Romulus

and Remus suckled by a wolf. (f) Coin commemorating the completion of the

Colosseum.

|

|

The Chinese warring

states each cast their own bronze coins. They came in four basic types:

Knife coins; spade coins with pointed or rounded shoulders; small shell-like

coins; disc coins. The last type was used mainly in Qin. After Qin

conquered the other states and united China, it standardized coinage. The

Han Dynasty adopted Qin’s design, varying only the weight. The Han coin,

shown disproportionately large, is a disc with a square hole, with a raised

lip on the edge and inscription of the weight. The hole facilitates

stringing these small-denomination coins into larger units. It became the

basic design for two millennia in imperial China.

|

|

The early Roman Republic and early Qin-Han

Dynasty were economies of small free holders who tilled their own land.

With the widening of the wealth inequality gap, many peasants lost their

farm and became tenant farmers. Here are two rent-collecting scenes. Notice

two differences. First, the Roman tenant paid his rent in money, the

Chinese paid in kind. Second, the account records held by the two landlords

show the different writing materials

in the two realms.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Roman rent collector.

|

|

|

|

4 Chinese rent collection.

|

|

|

Tomb relief showing a

tenant farmer bring in his rent, while the landlord checking his account

book of wax tablets. Second or third century. (Landesmuseum, Trier).

|

|

Tomb relief showing a

landlord sitting in front of his house, holding bamboo strips of account

record and watching tenants transferring grain from the cart to the

receiving measure. Latter Han. (Guanghan County Cultural Institution,

Sichuan).

|

|

|

The Roman and Chinese were both agrarian

economies, where more than eighty percent of the population engaged in

farming and related activities. Grain was the largest staple. The Romans were

also famous for the production of olive and wine, the Chinese for silk.

|

|

農戰

|

|

The plough and the lance are symbolic foundations of Roman

civilization. Farmer-soldiers won an empire for themselves. (Museum of

Roman Civilization, Rome).

|

“Farming and military readiness” was the policy of Shang Yang

(d. 338 BCE), whose reforms

changed Qin from a backward country to the unifier of China.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Third century mosaic

showing plowing. (Cherchel Museum, Algeria).

|

|

Rubbing of a tomb relief

showing ox-drawn plowing, which was becoming widespread in the Former Han

Dynasty. (Suining County,

Jiansu).

|

|

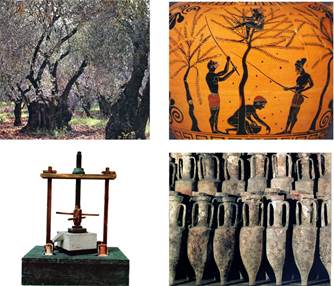

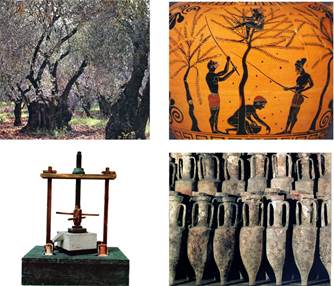

5 Olive oil production.

|

|

|

6. Silk production.

|

|

The olive grove was an

important economic source for the Greco-Roman world. At harvest, the

branches were beaten with long sticks. The fallen fruits were gathered and

pressed to make olive oil. Oil was stored and transported in amphorae, some

of which were recovered from sunken ships. Soil erosion was a big problem

if plantations were not properly managed.

|

|

Silkworm, the

caterpillar of the insect order Lepidoptera, is an eating machine of

mulberry leaves. After four molts, it produces a lustrous protein mixture

that hardens into a fiber, with which it makes a cocoon. Humans unravel the

cocoon by soaking it into hot water. Bundles of raw silk once served as a

kind of currency along the early Silk Route.

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. Wine production.

|

|

|

8. Textile production.

|

|

|

|

Mosaic showing three steps of wine making: gathering grapes among

vine tendrils, bringing in the harvest, and treading the vintage. Fourth

century. (Santa Costanza, Rome.)

|

|

Rubbing of tomb relief

showing a woman twisting silk yarns (right), another interlacing the

threads with a weft wheel (middle), and a third weaving with a loom. Latter Han. (Xuzhou, Jiangsu).

|

|

9. Roman fishermen.

|

|

|

|

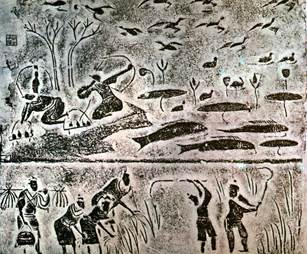

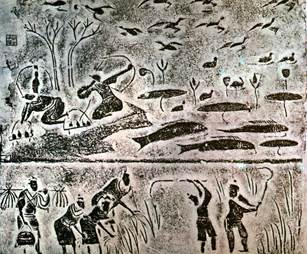

10. Chinese farmers, hunters, and fishermen.

|

|

|

Fishing with a net.

Detail of a second-century mosaic from Hadrumetum, Tunisia.

|

|

Fishing and hunting

supplements farming for food. Latter Han tomb chamber decoration.

(Chengdu).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Market places were bustling in both realms.

Commerce in the Qin-Han Dynasty was mainly confined to designated markets.

Shops also lined streets in Roman cities.

|

|

11. A Roman shop.

|

|

|

|

12. A Chinese wine shop.

|

|

|

A market scene on a relief in Ostia, the port of Rome. Second

century. (Roger-Viollet, Paris).

|

|

A wine shop on a tomb

relief in Peng County,

Sichuan. Latter Han. (Xindu County Cultural Bureau).

|

|