|

Roman and Chinese military systems

Military system was a big difference between the Roman and early

Chinese Empires. A peace-time standing army, some 300,000 strong, mostly

life-time professionals, was a peculiarity of the Roman Empire. A pillar of

the empire, it also became a source of political instability, as officer

cabals gradually developed a taste of hailing their own emperors. The Qin and

Former Han Dynasties, like the Roman Republic, depended on conscription.

Rotating draftees serving year-long tours filled the main army when military

needs arose. With their better developed civilian bureaucracy, the court had

better control of the army.

|

|

1. Trajan conquering Parthia.

|

|

|

|

2. A tally for commanding troop movements.

|

|

|

Coin issued by Trajan in

115 CE, the year he reached the Persian Gulf. Trajan personally led the

army in conquering Dacia and Mesopotamia. After his precedent, Roman

emperors were obliged to campaign in person. When hostilities erupted in

several fronts, the inability of the emperor to be everywhere often

prompted usurpers.

|

|

A tiger-shaped tally by

which the First Emperor moved particular units, this one for the troops in Yangling.

The inscription says: “Military tally. The right side stays with the

emperor, the left side stays in Yangling.” The troops obeyed commands only

when the two matched sides combined. Such tallies had been in used since

the warring-states period.

|

|

|

Infantry was always the main force of the

Roman army. It displaced chariots on Chinese battlefields since the

warring-states period.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A legionary of the first

century BCE, armed with javelin, sword, and shield.

|

|

A Qin infantryman,

probably holding sword and halberd.

|

|

|

3. Roman swords.

|

|

|

|

4. Weapons for Qin's infantrymen.

|

|

|

A dagger and a sword in

the style of gladius hispaniensis or

Spanish stabbing sword, on which Roman legionary swords were based.

|

|

Drawing of Qin weapons:

a sword; a halberd, and a spear.

The halberd was the favorite.

|

|

|

5. The Roman tortois formation.

|

|

|

6. A terracotta soldier with crossbow.

|

|

|

Fighting with locked shields,

which required great cooperative discipline, was a characteristic of the

Greco-Roman army. A supreme expression was the Roman testudo (tortoise)

formation that protected soldiers from missiles. The picture illustrates

its use in attacking a fort.

|

|

The crossbow was a

favorite weapon of the Chinese infantry. Drawn with the help of legs, it was stronger than arm-drawn bows. Its

mechanical trigger increased accuracy. Requiring less skill, it could be

deployed en mass, which compensated for its rather low firing rate.

|

|

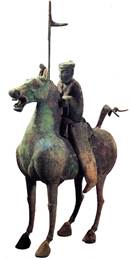

7. A Roman cavalryman.

|

|

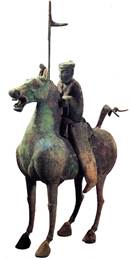

8. A Han cavalryman.

|

|

(Museum of Roman

Civilization, Rome).

|

|

(Burial

object, Latter Han).

|

|

9. A Roman crushing a Gaul.

|

|

|

10. The Parthian shot in China.

|

|

|

Sarcophagus relief of a

fourth century cavalry general in Gaul. Auxiliaries made up the bulk of the

Roman cavalry. Like contemporaneous Chinese, the Romans lacked stirrups.

|

|

Detail of a Latter Han

tomb relief showing a Chinese horseman executing what the Romans called the

“Parthian shot”. Wars with northern nomads prompted the Chinese to practice

mounted archery.

|

|

|

|

Battle scenes

appear in Roman artworks of all kinds, as they receive thick descriptions

in historiography. In contrast, they are rarely found in Chinese art and

historiography.

|

|

11. Details of Trajan's Column.

|

|

12. Warring-states vessel showing

battle scenes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Details from Trajan’s column and the

column of Marcus Aurelius. Besides fighting and killing captives, the

triumphant columns also show soldiers engaging in constructive

activities.

|

|

A bronze vassal of the warring-states

period depicts hunting, music playing, and other daily activities on the

upper part, and on the lower, land, river, and siege warfare.

|

Rome’s large professional army constituted a world of its own. Its

basis on the northern frontier seeded major European cities: Cologne, Bonn, Mainz, Vienna, Budapest, and Belgrade. The

Chinese northern and northwestern frontier was in more desolate terrains.

It defense relied more on civilian settlers and militia. Even garrison troops

were often accompanied by families.

|

13. A Roman fort defending

Cologne.

|

|

14. The Jade Gate.

|

|

Model of Fort Deutz defending Cologne, which became a military

base in 50 BCE.

|

|

Remains of the Jade Gate, which is deserted even by modern

tourists of the Silk Road.

|

|

15. The ruins of Roman fortress.

|

|

16. From the life of garrisons on

the Silk Road.

|

|

The foundation remains of a legionary fortress at Caerleon, South

Wales. Serving the barracks are networks of waterworks and latrines.

|

|

Items recovered from the site of a Former Han beacon tower 95 km

from Dunhuang: A doll’s garment, a child’s shoe, an identification tag, a

comb, and a piece of flax paper with writing brush.

|

|

|

17. A legionary camp on the Hadrian Wall.

|

|

|

|

18. A farmer-soldier camp on the great wall.

|

|

|

|

Aerial view of Hadrian’s

Wall at Vercovicium in Britain, with a fort attached to its south side.

(Jason Hawkes).

|

|

Arial view of the First Emperor’s

wall in Guyang, Inner Mongolia. Its height and width are puny compared to

the familiar Great Wall built in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1661).

|

|